EXHIBITION: CHAMBERLAIN ET AL.

December 1991 – January 1992

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

Within the parameters suggested by the works included in this exhibition, John Chamberlain becomes a key figure. His early interest in gesture, which remains a central aspect of his current work, developed out of his strong feelings for the ground breaking work of the Abstract-Expressionists. By working in sculpture, Chamberlain was able to shift gesture from a two dimensional domain to a three dimensional one. At the same time, his use of car parts, their pliable metal shells and parts, anticipates a subsequent generation's use of "things" found in the urban-industrial landscape, and, later, the use of the landscape as it was found. Certainly, both the "things" in his landscape and the landscape itself were central to younger artists, such as Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson.

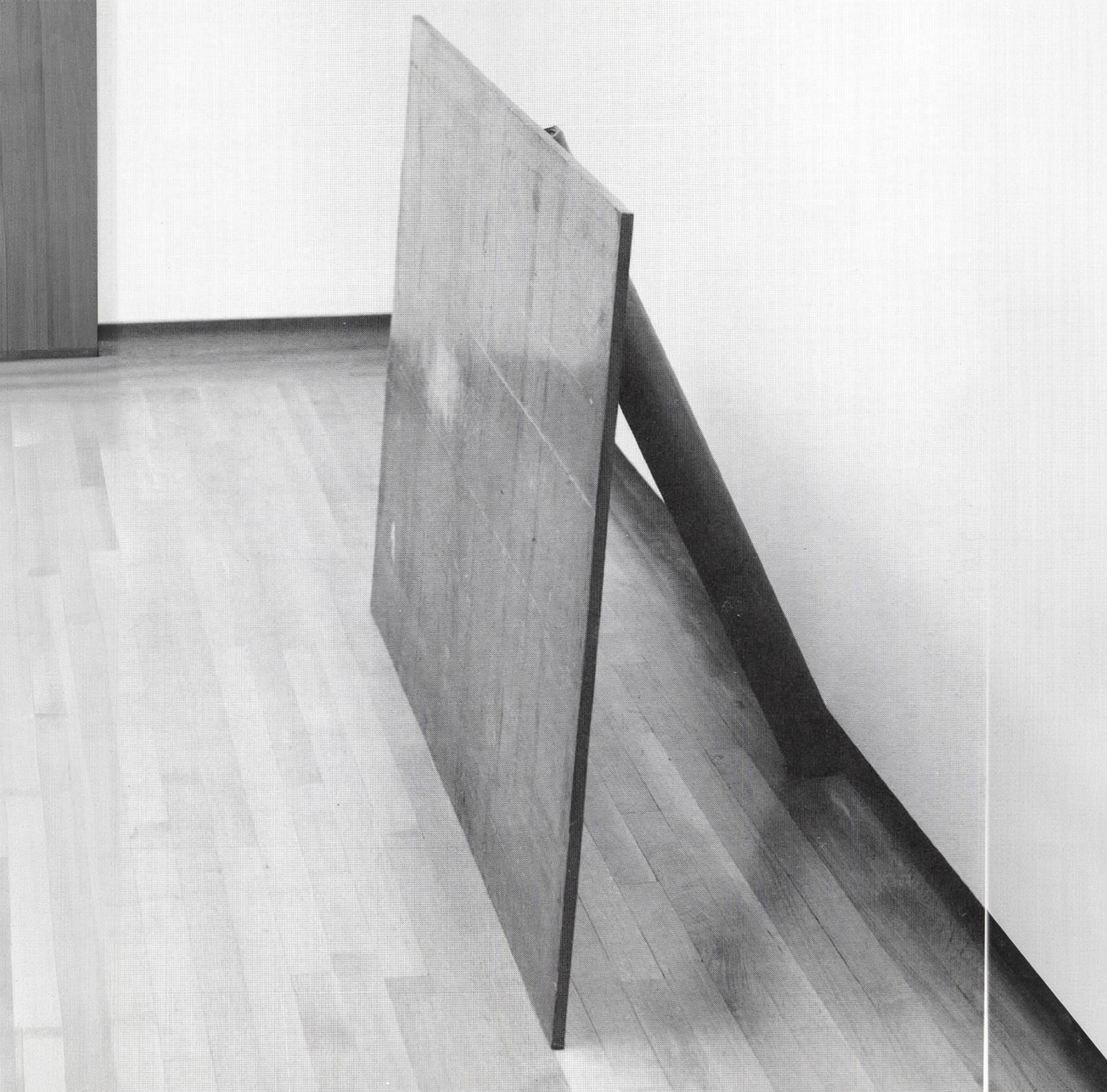

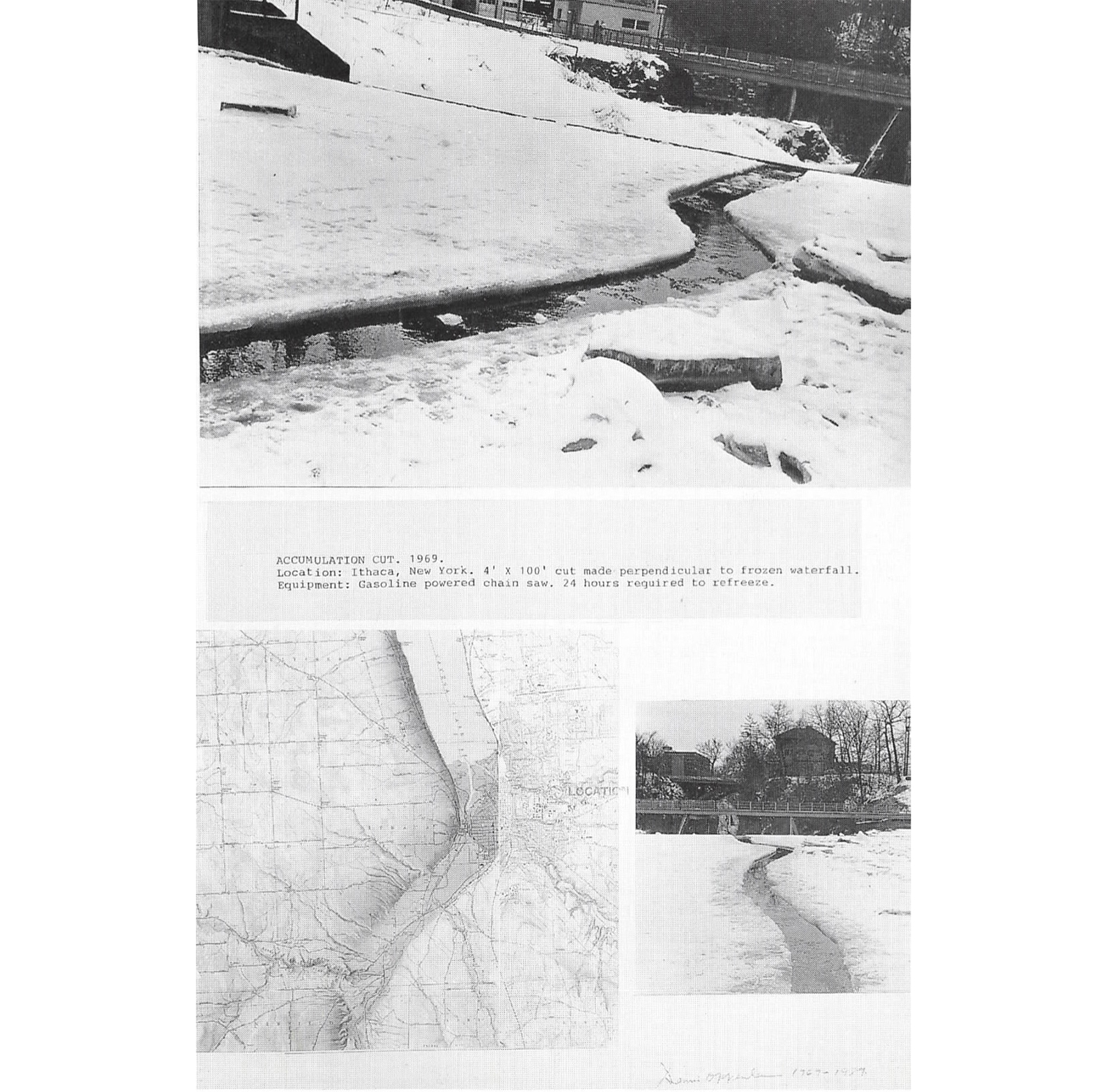

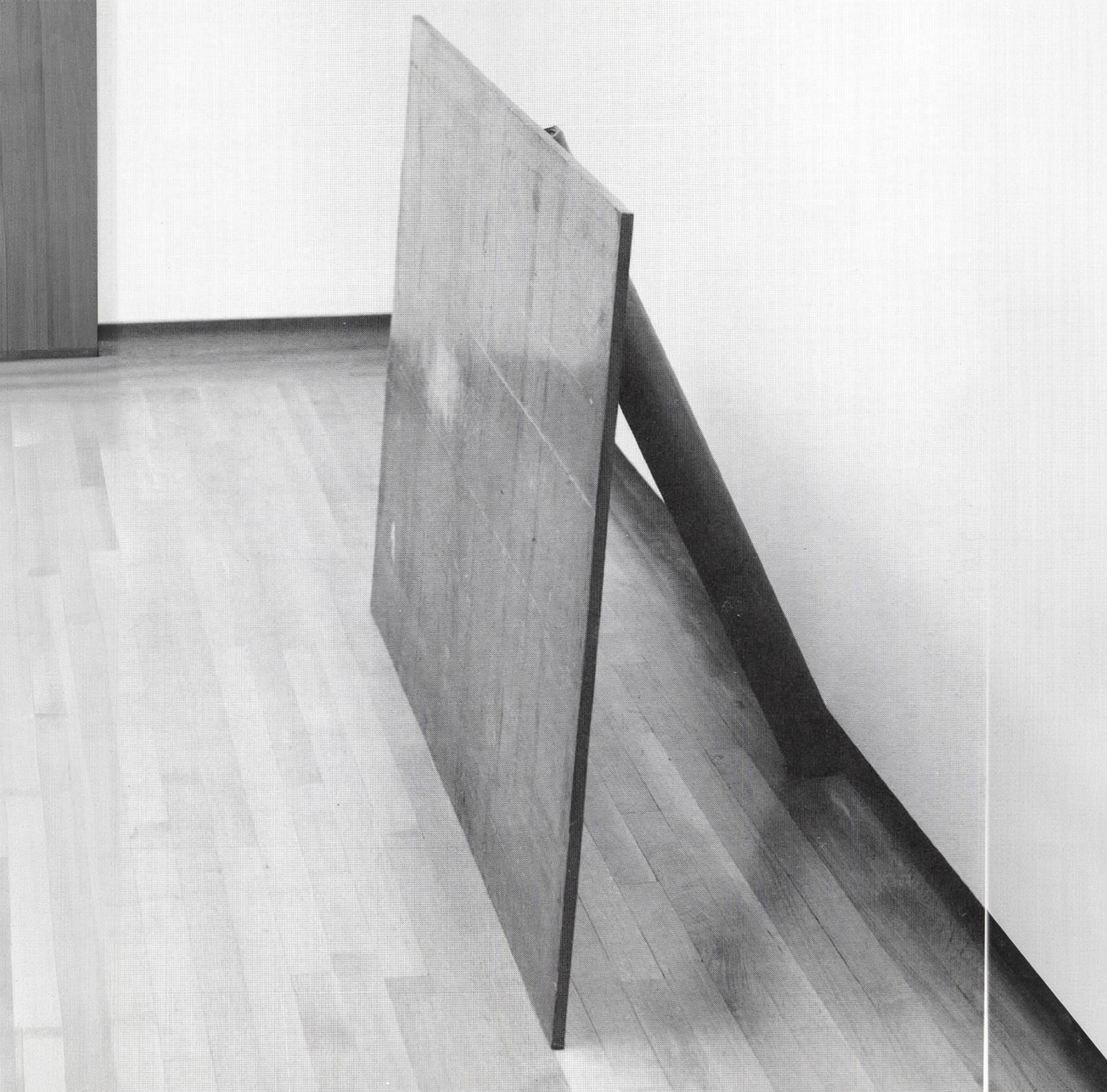

Along with Chamberlain, Richard Serra, particularly in his early work, was influenced by the Abstract-Expressionists, especially Jackson Pollock, who was able to transform his entire body's motions into arabesques of paint. Serra's "splashings" of hot lead in the late 1960's can be seen as both a brilliant restating of Pollock's painterly methods as well as a bridge to a younger generation of artists. At the same time, his Led Piece, 1969, is a form which underscores the flexibility of lead as well as evokes the principal element used in rationalistic architecture. For Serra, gesture was no longer seen as a record of transcendent yearning, but as self-reflexive "thing." Moreover, the interplay between sculpture and site, which has characterized much of Serra's work since his "splashings," connects him to Harris, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, and Smithson, all of whom made work which recontextualized a specific landscape, whether it was a pristine gallery space, an abandoned Manhattan pier, a frozen lake in upstate New York, or New Jersey's decaying industrial landscape. And within this dance of possibilities, Weiner's work brings the viewer back into the world, makes them reconsider their interaction with it.

Starting in the late 1960's, a number of artists began questioning the framework in which art was seen. For some the framework was the gallery or museum, while others found the commodification of art disturbing. Conscious of the repressive nature of these various frames, artists such as Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, Serra, Smithson, and Weiner made work which questioned the different, historically accepted frameworks in which art was placed. In making or placing work which proposed a relationship between the object, be it made of lead or words stenciled or painted on a wall, and the place it was in, these artists revealed the unstable and often repressive nature of all culturally accepted environments or contexts. Rather than making work which accepted the world as a collection of fixed places, they attempted to reveal the various ways the world is constantly in a state of flux, a state of decay and regeneration.

Smithson incorporated entropic processes into many of his works, Matta-Clark called what he was doing "Anarchitecture," Oppenheim worked with changing landscapes such as a farmer's field or a frozen lake, and Weiner stenciled words onto a wall, which proposed an interaction with things in the world. In this case, the viewer becomes the "artist," the one who must contextualize Weiner's words, and in doing, reflect upon one's gestures. Instead of making work which would be placed somewhere, on a wall or in a room or a park, these artists examined, undermined, and refocused aspects of the environment in order to point out, among other things, that art does not exist apart from the world, that the exalted notion that art is in and of itself self-sufficient and permanent is neither useful nor valid.

II.

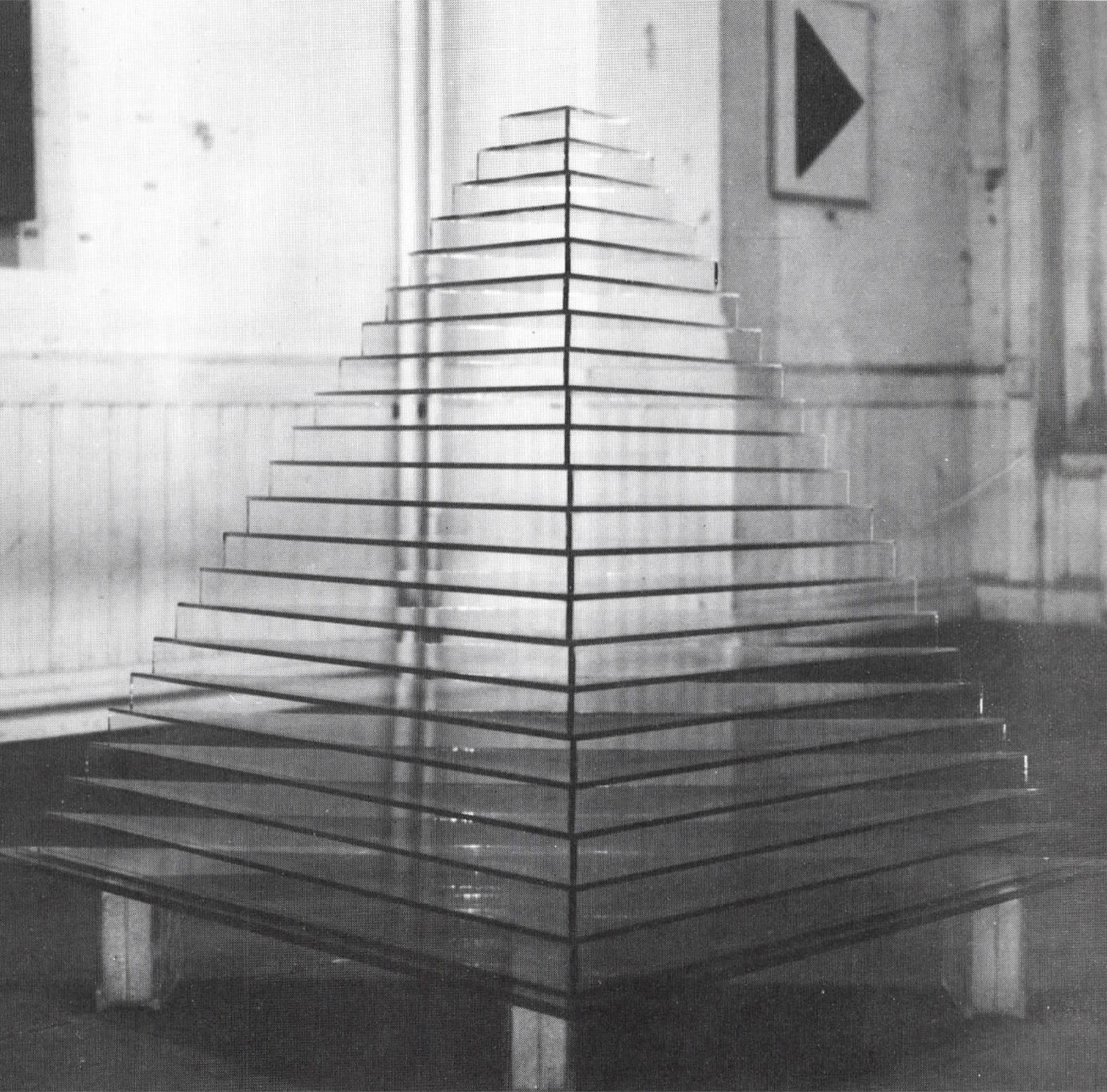

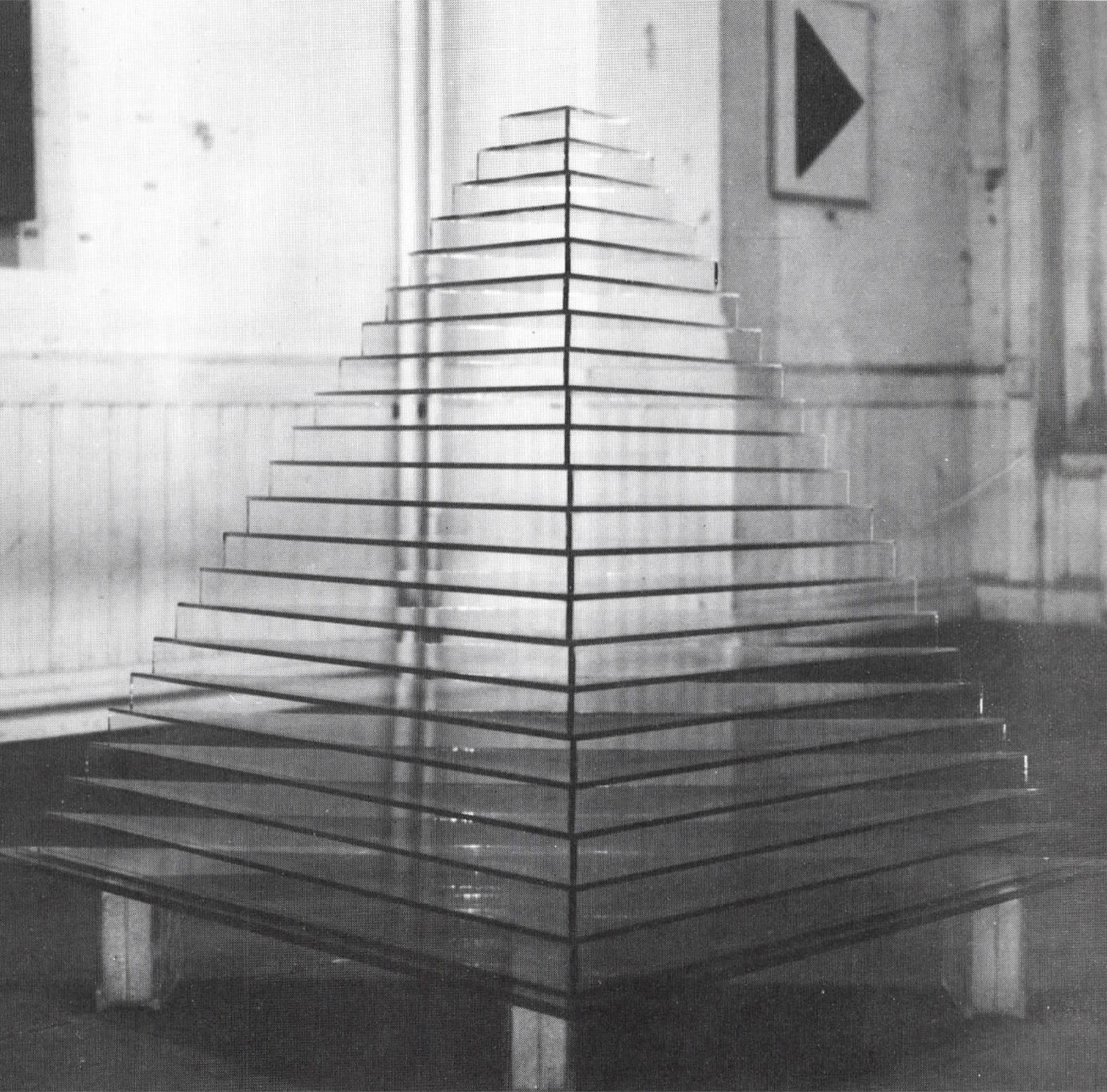

Although the works in this exhibition are very different, there are certain properties which they share. For these artists, the physical or natural world is no longer seen as evidence of purity and spiritual presence. Their use of non-art materials- stencils, car parts, lead sheets, glass, mirrors, a portion of an office building's floor and ceiling, and photographs- convey something about the tangible world we inhabit, while also evoking an air of danger and instability. For example, the inherently fragile nature of glass in Suzanne Harris' work and the possible danger raised by Matta-Clark's placement of one section of his piece on the ceiling above the viewer's head, tell the viewer the world is constantly transforming itself in visible and invisible ways. In retrospect, one can now see that between the late '60's and early '70's, the crashing cascades of paint, scarred and scraped surfaces, and uncontainable fields of expanding gestures that characterized the paintings of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, had given way to an altogether different possibility.

III.

Common to all of the work in this exhibition is the artist's clear sighted attempt to analyze, dissect, and reconstitute the physical structures and familiar paradigms of "reality" he or she (and by extension the viewer) live inside of. There is a feeling of discontent in the work, a sense that the artists find the cultural institutions stifling environments for art making. Their insistent efforts to exert some control over the interplay between art and its environment broadens our understanding of art as well as the world we inhabit. Thus, whether these artists are overtly socially conscious or not, there is within their work a challenge to see "reality" differently, not the "reality" of art or of art history, but of that which is common; the actual world.

It is this insistence on the actual, not as a pure form but as forms made out of impure materials, out of such "things" as mirrors, wooden floors, and words, that unites these artists. Serra's lead piece and Harris' pyramid are forms derived from architecture's vocabulary, while Chamberlain, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim and Smithson bring "things" from the world into the gallery. It is the world out there, one that all of these artists interact with through their work, that Weiner directs out attention to. Although more than two decades have passed since much of this work was made, and much has happened in art since then, the dialogue between art and context these artists established seems as timely, provocative, and challenging as it did then. It is not simply that this work reminds us that not all is right with the world, but that it continues to reveal something about the conditions we still occupy.

John Yau, November 1991

EXHIBITION: CHAMBERLAIN ET AL.

December 1991 – January 1992

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

Within the parameters suggested by the works included in this exhibition, John Chamberlain becomes a key figure. His early interest in gesture, which remains a central aspect of his current work, developed out of his strong feelings for the ground breaking work of the Abstract-Expressionists. By working in sculpture, Chamberlain was able to shift gesture from a two dimensional domain to a three dimensional one. At the same time, his use of car parts, their pliable metal shells and parts, anticipates a subsequent generation's use of "things" found in the urban-industrial landscape, and, later, the use of the landscape as it was found. Certainly, both the "things" in his landscape and the landscape itself were central to younger artists, such as Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson.

Along with Chamberlain, Richard Serra, particularly in his early work, was influenced by the Abstract-Expressionists, especially Jackson Pollock, who was able to transform his entire body's motions into arabesques of paint. Serra's "splashings" of hot lead in the late 1960's can be seen as both a brilliant restating of Pollock's painterly methods as well as a bridge to a younger generation of artists. At the same time, his Led Piece, 1969, is a form which underscores the flexibility of lead as well as evokes the principal element used in rationalistic architecture. For Serra, gesture was no longer seen as a record of transcendent yearning, but as self-reflexive "thing." Moreover, the interplay between sculpture and site, which has characterized much of Serra's work since his "splashings," connects him to Harris, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, and Smithson, all of whom made work which recontextualized a specific landscape, whether it was a pristine gallery space, an abandoned Manhattan pier, a frozen lake in upstate New York, or New Jersey's decaying industrial landscape. And within this dance of possibilities, Weiner's work brings the viewer back into the world, makes them reconsider their interaction with it.

Starting in the late 1960's, a number of artists began questioning the framework in which art was seen. For some the framework was the gallery or museum, while others found the commodification of art disturbing. Conscious of the repressive nature of these various frames, artists such as Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, Serra, Smithson, and Weiner made work which questioned the different, historically accepted frameworks in which art was placed. In making or placing work which proposed a relationship between the object, be it made of lead or words stenciled or painted on a wall, and the place it was in, these artists revealed the unstable and often repressive nature of all culturally accepted environments or contexts. Rather than making work which accepted the world as a collection of fixed places, they attempted to reveal the various ways the world is constantly in a state of flux, a state of decay and regeneration.

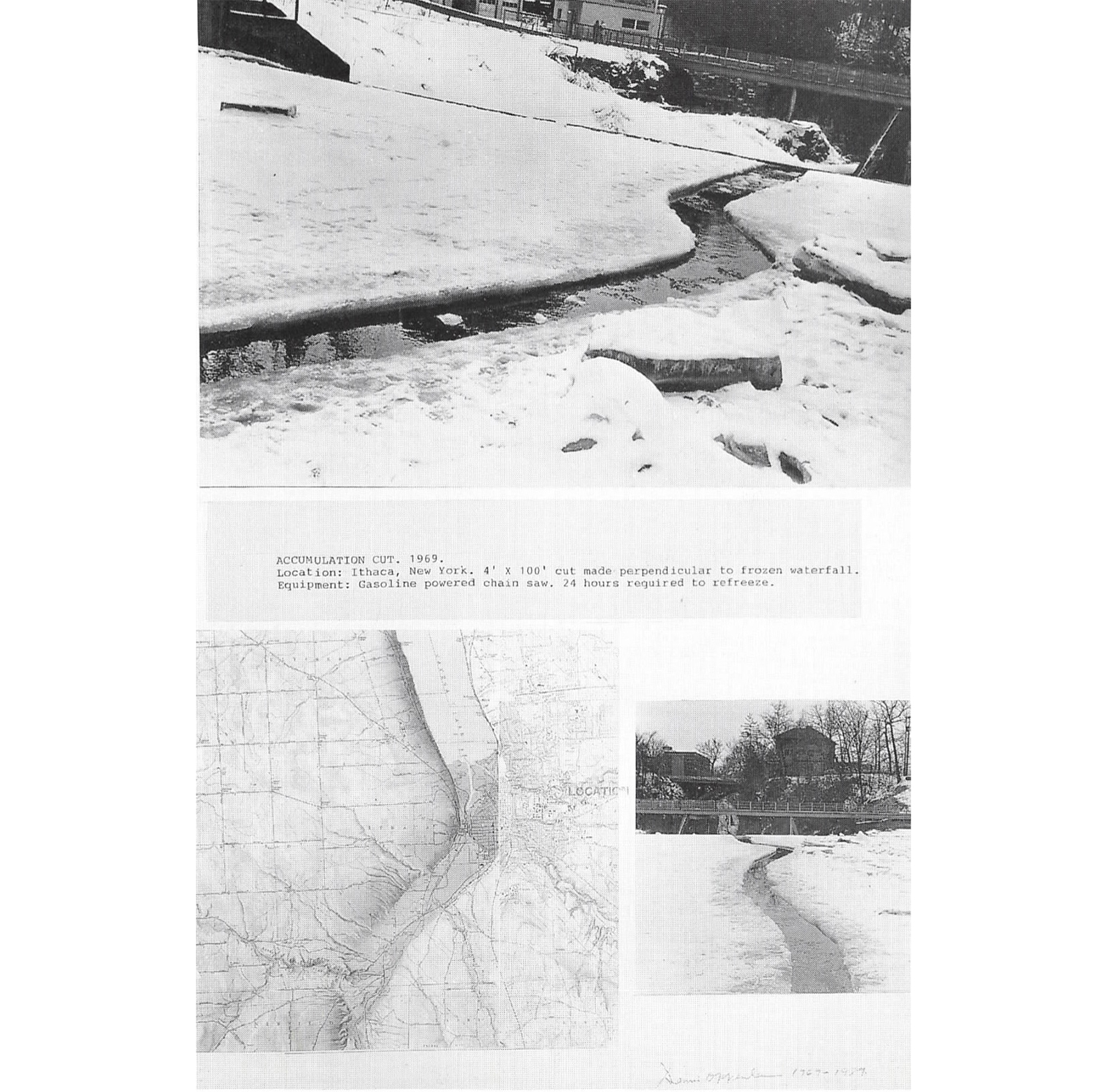

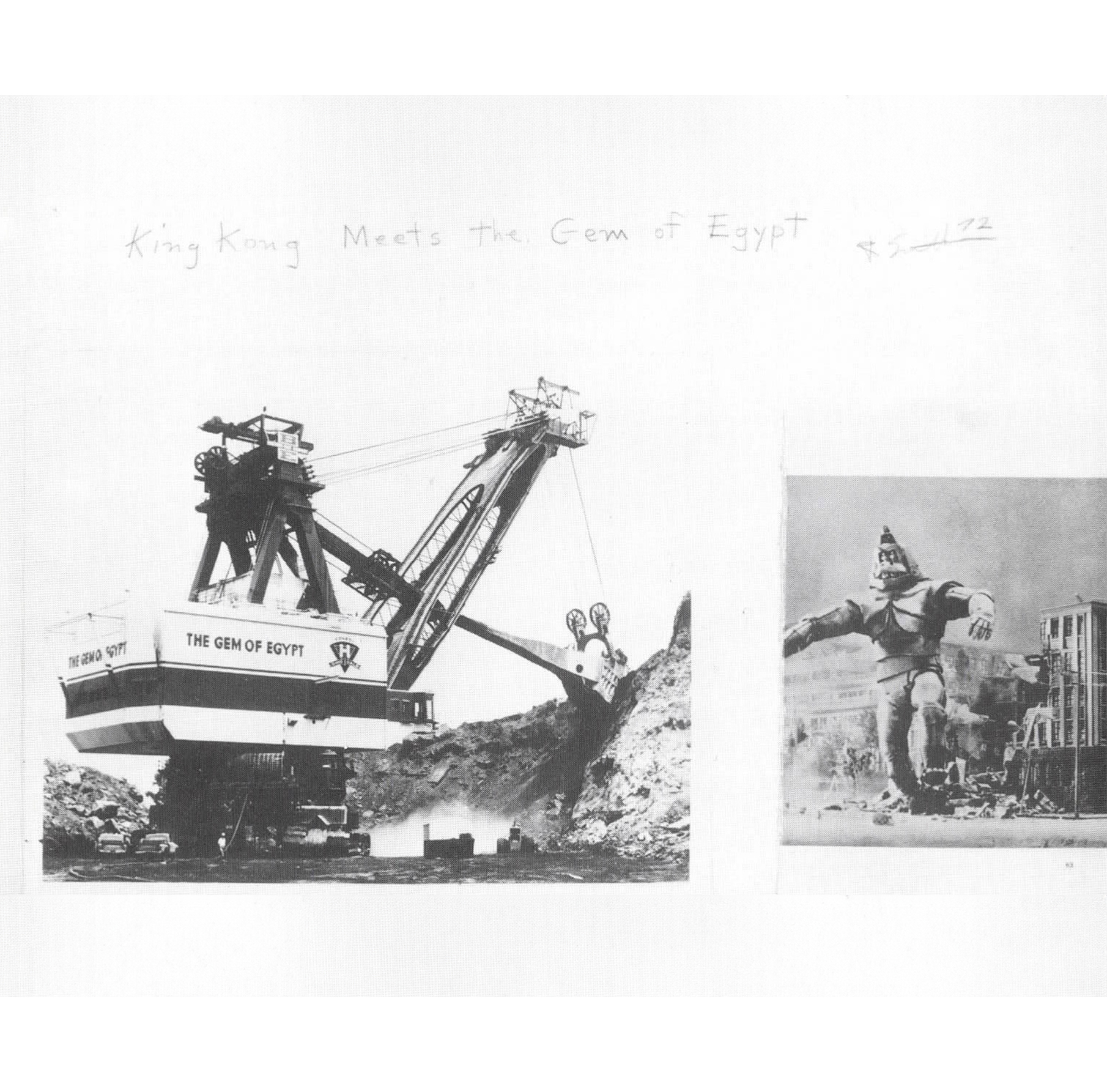

Smithson incorporated entropic processes into many of his works, Matta-Clark called what he was doing "Anarchitecture," Oppenheim worked with changing landscapes such as a farmer's field or a frozen lake, and Weiner stenciled words onto a wall, which proposed an interaction with things in the world. In this case, the viewer becomes the "artist," the one who must contextualize Weiner's words, and in doing, reflect upon one's gestures. Instead of making work which would be placed somewhere, on a wall or in a room or a park, these artists examined, undermined, and refocused aspects of the environment in order to point out, among other things, that art does not exist apart from the world, that the exalted notion that art is in and of itself self-sufficient and permanent is neither useful nor valid.

II.

Although the works in this exhibition are very different, there are certain properties which they share. For these artists, the physical or natural world is no longer seen as evidence of purity and spiritual presence. Their use of non-art materials- stencils, car parts, lead sheets, glass, mirrors, a portion of an office building's floor and ceiling, and photographs- convey something about the tangible world we inhabit, while also evoking an air of danger and instability. For example, the inherently fragile nature of glass in Suzanne Harris' work and the possible danger raised by Matta-Clark's placement of one section of his piece on the ceiling above the viewer's head, tell the viewer the world is constantly transforming itself in visible and invisible ways. In retrospect, one can now see that between the late '60's and early '70's, the crashing cascades of paint, scarred and scraped surfaces, and uncontainable fields of expanding gestures that characterized the paintings of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, had given way to an altogether different possibility.

III.

Common to all of the work in this exhibition is the artist's clear sighted attempt to analyze, dissect, and reconstitute the physical structures and familiar paradigms of "reality" he or she (and by extension the viewer) live inside of. There is a feeling of discontent in the work, a sense that the artists find the cultural institutions stifling environments for art making. Their insistent efforts to exert some control over the interplay between art and its environment broadens our understanding of art as well as the world we inhabit. Thus, whether these artists are overtly socially conscious or not, there is within their work a challenge to see "reality" differently, not the "reality" of art or of art history, but of that which is common; the actual world.

It is this insistence on the actual, not as a pure form but as forms made out of impure materials, out of such "things" as mirrors, wooden floors, and words, that unites these artists. Serra's lead piece and Harris' pyramid are forms derived from architecture's vocabulary, while Chamberlain, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim and Smithson bring "things" from the world into the gallery. It is the world out there, one that all of these artists interact with through their work, that Weiner directs out attention to. Although more than two decades have passed since much of this work was made, and much has happened in art since then, the dialogue between art and context these artists established seems as timely, provocative, and challenging as it did then. It is not simply that this work reminds us that not all is right with the world, but that it continues to reveal something about the conditions we still occupy.

John Yau, November 1991

EXHIBITION: CHAMBERLAIN ET AL.

December 1991 – January 1992

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

I.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, there are many who still believe the world is a solid and stable place. The fact that there continues to be an argument between those who propose that we all participate in a common "reality" and those who recognize that everything, even the recognizer, is in a state of transition, makes this exhibition both challenging and timely. Connected in various ways to each other, as well as to the esthetic currents that proliferated between the late 1960's and mid 1970's, the artists whose works are included in this exhibition were among the first to dissect, analyze, and upend the "reality" we all supposedly shared. That they belong to different generations and articulate their work out of different kernels of thought and feeling should not, however, prevent us from beginning to see the various affinities, lines of thought, dispositions, and attitudes that they shared. For behind the significant differences in their work were certain overlapping topologies: racial strife, sexual prejudices, the Vietnam War, Watergate, the inability of America to either solve or hide its deepening social inequities, and the disturbing realization that what we were given to see was not necessarily what was there.

The artists- John Chamberlain, Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and Lawrence Weiner- have generally been understood in relationship to artistic movements and critical discourses such as Earth Art, Minimalism, Post-Minimalism, and Conceptual Art. While these terms may have been initially useful during the specific period in which they were first used to name various actions and kinds of work, to continue to use them is to tilt this critical enterprise toward neat categories and the fixity of historical periods, esthetic modes of perception that at the very best are false and misleading. It is not only the world, either this one now or the one that was then, that is contingent, but also our relationship to it. The world is always far messier and elusive than any category we place on top of it. Rather, like Gordon Matta-Clark, who dug a hole in the floor of his gallery in an attempt to expose its foundation, an act of baring the very ground one stands on, it might best serve the purposes of this exhibition to uncover the affinities and relationships, while also respecting the spaces between those affinities and relationships.

Within the parameters suggested by the works included in this exhibition, John Chamberlain becomes a key figure. His early interest in gesture, which remains a central aspect of his current work, developed out of his strong feelings for the ground breaking work of the Abstract-Expressionists. By working in sculpture, Chamberlain was able to shift gesture from a two dimensional domain to a three dimensional one. At the same time, his use of car parts, their pliable metal shells and parts, anticipates a subsequent generation's use of "things" found in the urban-industrial landscape, and, later, the use of the landscape as it was found. Certainly, both the "things" in his landscape and the landscape itself were central to younger artists, such as Suzanne Harris, Gordon Matta-Clark, Dennis Oppenheim, Richard Serra, and Robert Smithson.

Along with Chamberlain, Richard Serra, particularly in his early work, was influenced by the Abstract-Expressionists, especially Jackson Pollock, who was able to transform his entire body's motions into arabesques of paint. Serra's "splashings" of hot lead in the late 1960's can be seen as both a brilliant restating of Pollock's painterly methods as well as a bridge to a younger generation of artists. At the same time, his Led Piece, 1969, is a form which underscores the flexibility of lead as well as evokes the principal element used in rationalistic architecture. For Serra, gesture was no longer seen as a record of transcendent yearning, but as self-reflexive "thing." Moreover, the interplay between sculpture and site, which has characterized much of Serra's work since his "splashings," connects him to Harris, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, and Smithson, all of whom made work which recontextualized a specific landscape, whether it was a pristine gallery space, an abandoned Manhattan pier, a frozen lake in upstate New York, or New Jersey's decaying industrial landscape. And within this dance of possibilities, Weiner's work brings the viewer back into the world, makes them reconsider their interaction with it.

Starting in the late 1960's, a number of artists began questioning the framework in which art was seen. For some the framework was the gallery or museum, while others found the commodification of art disturbing. Conscious of the repressive nature of these various frames, artists such as Matta-Clark, Oppenheim, Serra, Smithson, and Weiner made work which questioned the different, historically accepted frameworks in which art was placed. In making or placing work which proposed a relationship between the object, be it made of lead or words stenciled or painted on a wall, and the place it was in, these artists revealed the unstable and often repressive nature of all culturally accepted environments or contexts. Rather than making work which accepted the world as a collection of fixed places, they attempted to reveal the various ways the world is constantly in a state of flux, a state of decay and regeneration.

Smithson incorporated entropic processes into many of his works, Matta-Clark called what he was doing "Anarchitecture," Oppenheim worked with changing landscapes such as a farmer's field or a frozen lake, and Weiner stenciled words onto a wall, which proposed an interaction with things in the world. In this case, the viewer becomes the "artist," the one who must contextualize Weiner's words, and in doing, reflect upon one's gestures. Instead of making work which would be placed somewhere, on a wall or in a room or a park, these artists examined, undermined, and refocused aspects of the environment in order to point out, among other things, that art does not exist apart from the world, that the exalted notion that art is in and of itself self-sufficient and permanent is neither useful nor valid.

II.

Although the works in this exhibition are very different, there are certain properties which they share. For these artists, the physical or natural world is no longer seen as evidence of purity and spiritual presence. Their use of non-art materials- stencils, car parts, lead sheets, glass, mirrors, a portion of an office building's floor and ceiling, and photographs- convey something about the tangible world we inhabit, while also evoking an air of danger and instability. For example, the inherently fragile nature of glass in Suzanne Harris' work and the possible danger raised by Matta-Clark's placement of one section of his piece on the ceiling above the viewer's head, tell the viewer the world is constantly transforming itself in visible and invisible ways. In retrospect, one can now see that between the late '60's and early '70's, the crashing cascades of paint, scarred and scraped surfaces, and uncontainable fields of expanding gestures that characterized the paintings of Kline, de Kooning, and Pollock, had given way to an altogether different possibility.

III.

Common to all of the work in this exhibition is the artist's clear sighted attempt to analyze, dissect, and reconstitute the physical structures and familiar paradigms of "reality" he or she (and by extension the viewer) live inside of. There is a feeling of discontent in the work, a sense that the artists find the cultural institutions stifling environments for art making. Their insistent efforts to exert some control over the interplay between art and its environment broadens our understanding of art as well as the world we inhabit. Thus, whether these artists are overtly socially conscious or not, there is within their work a challenge to see "reality" differently, not the "reality" of art or of art history, but of that which is common; the actual world.

It is this insistence on the actual, not as a pure form but as forms made out of impure materials, out of such "things" as mirrors, wooden floors, and words, that unites these artists. Serra's lead piece and Harris' pyramid are forms derived from architecture's vocabulary, while Chamberlain, Matta-Clark, Oppenheim and Smithson bring "things" from the world into the gallery. It is the world out there, one that all of these artists interact with through their work, that Weiner directs out attention to. Although more than two decades have passed since much of this work was made, and much has happened in art since then, the dialogue between art and context these artists established seems as timely, provocative, and challenging as it did then. It is not simply that this work reminds us that not all is right with the world, but that it continues to reveal something about the conditions we still occupy.

John Yau, November 1991

ARTISTS

ARTISTS

ARTISTS

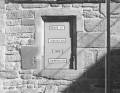

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Office Baroque, 1977

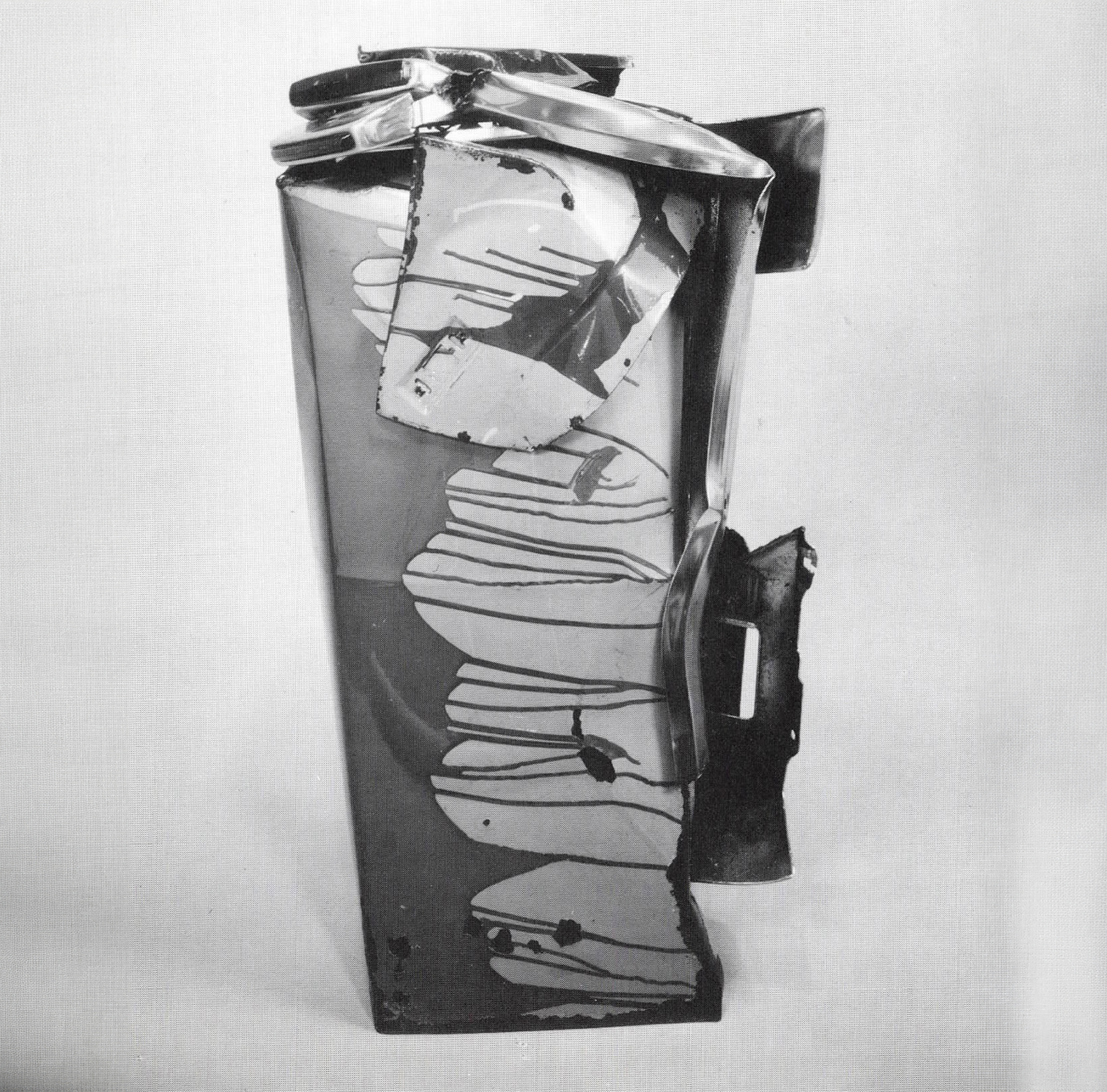

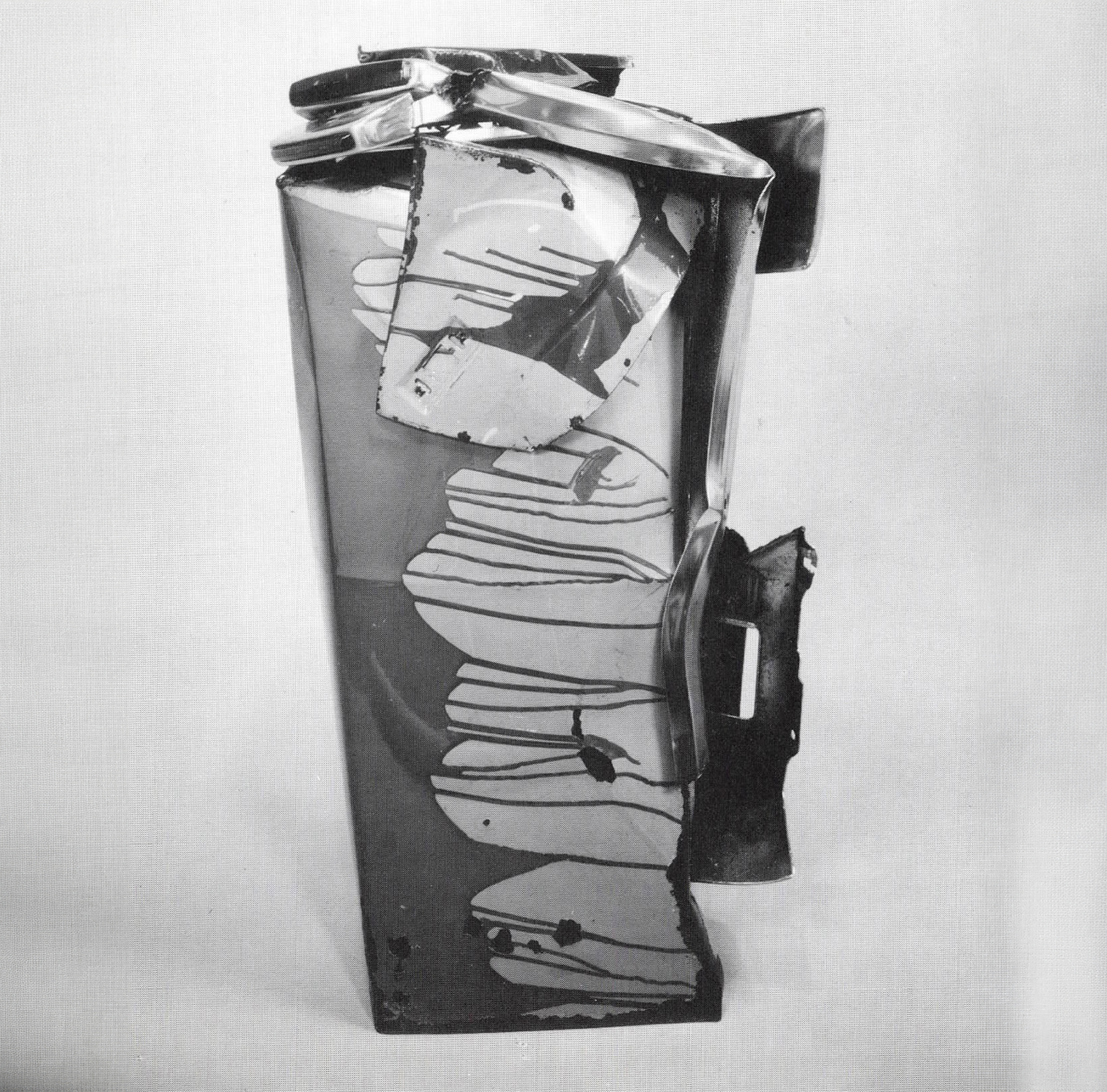

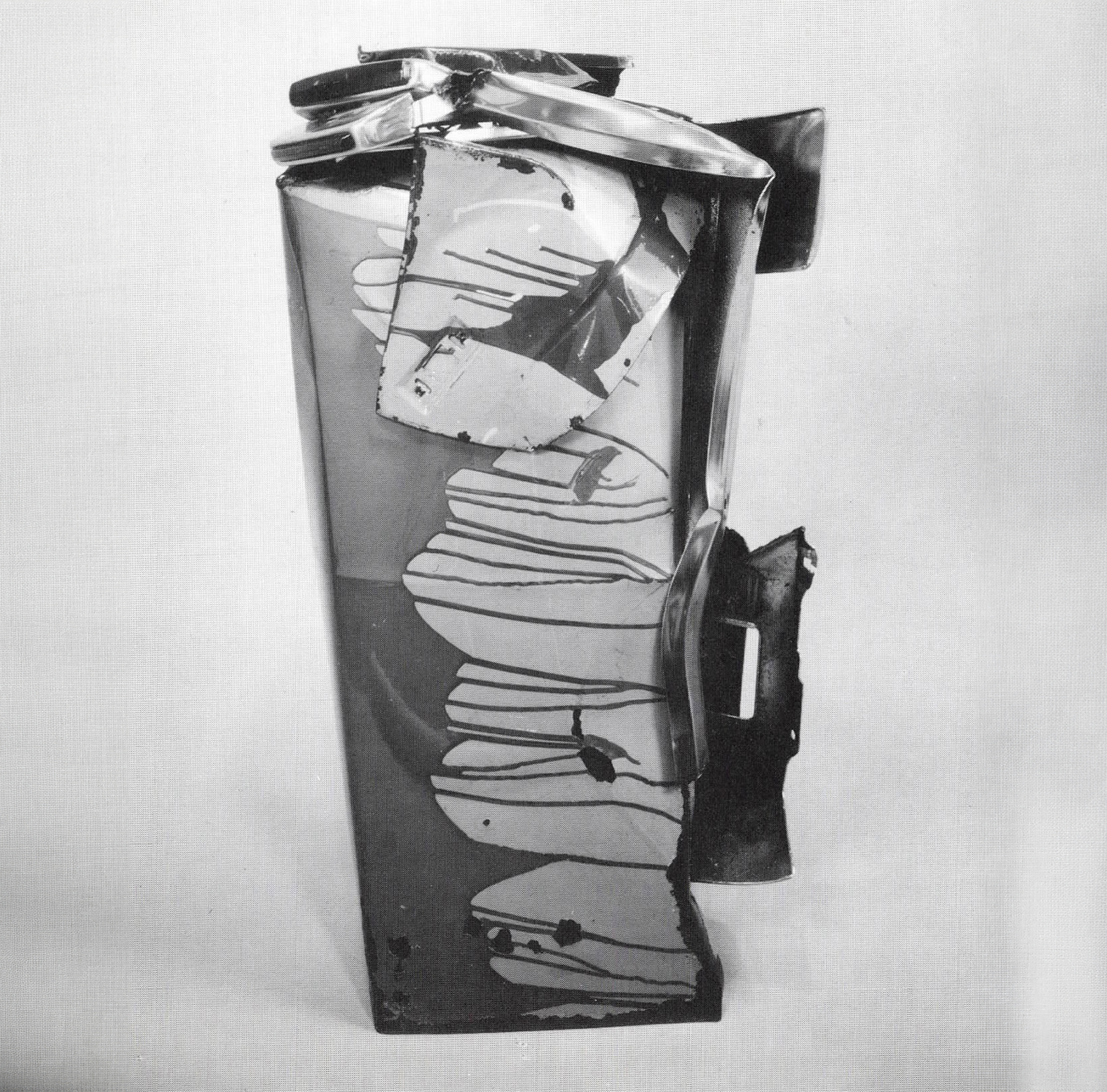

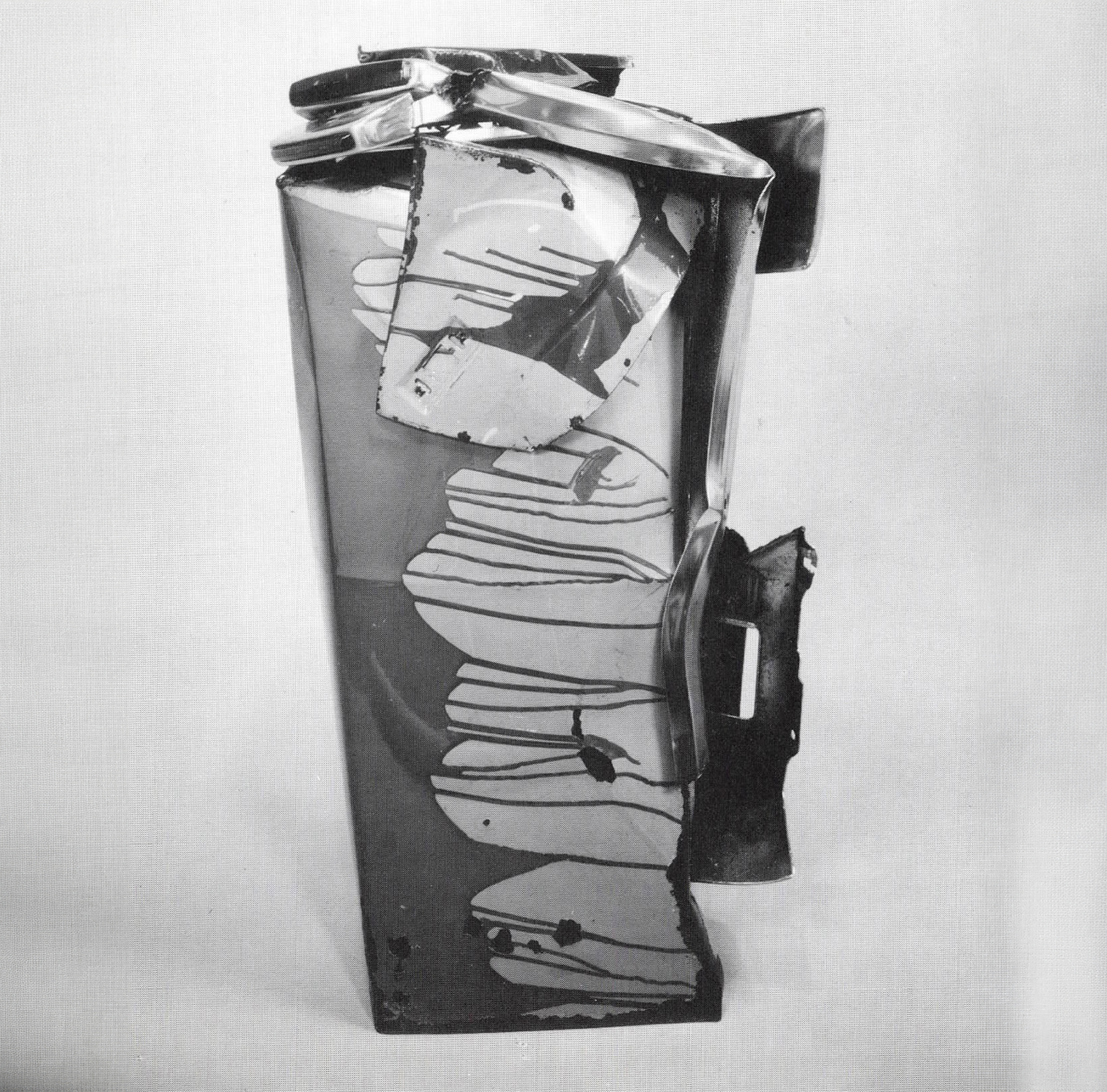

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

Different Henry, 1974

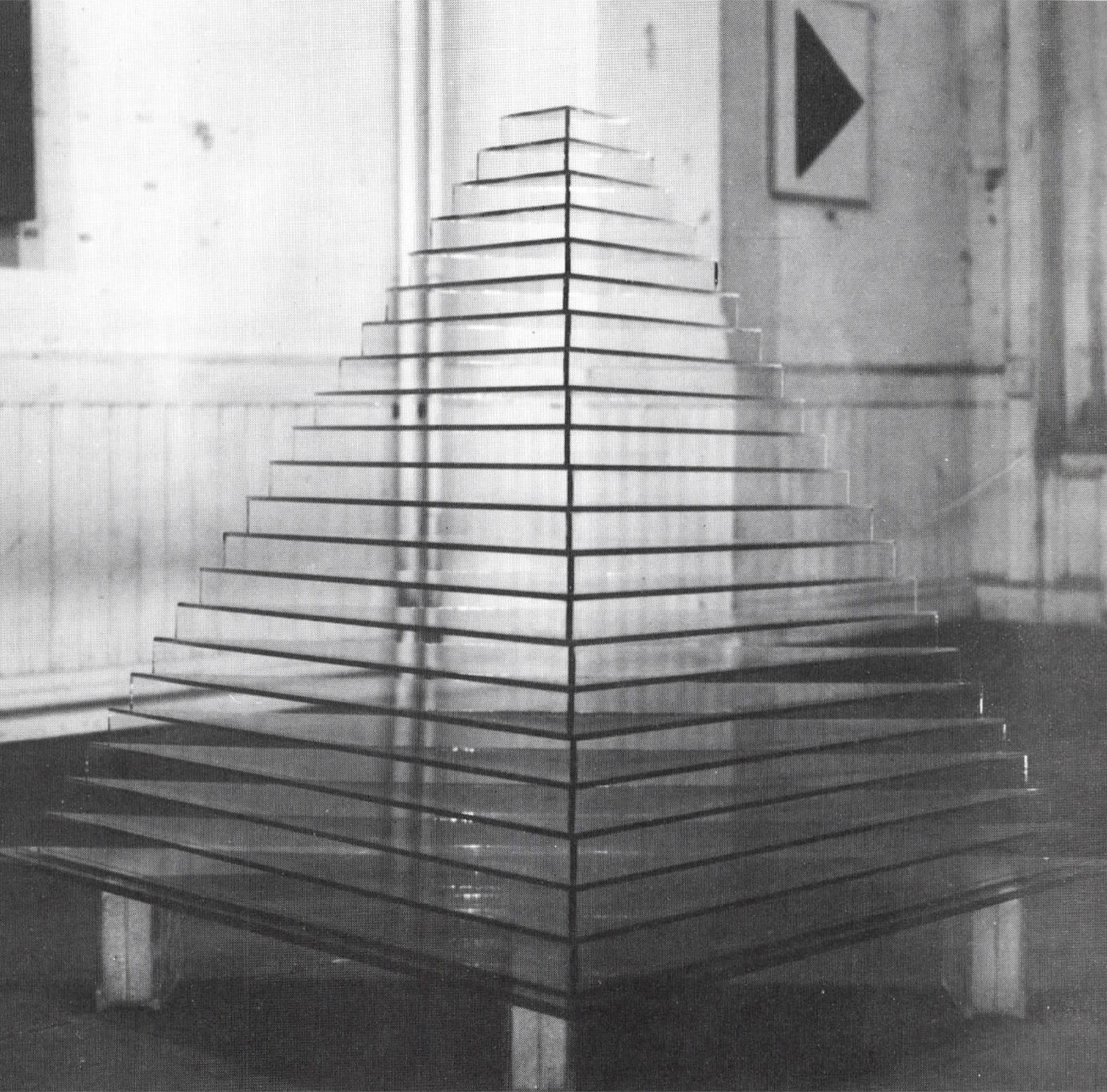

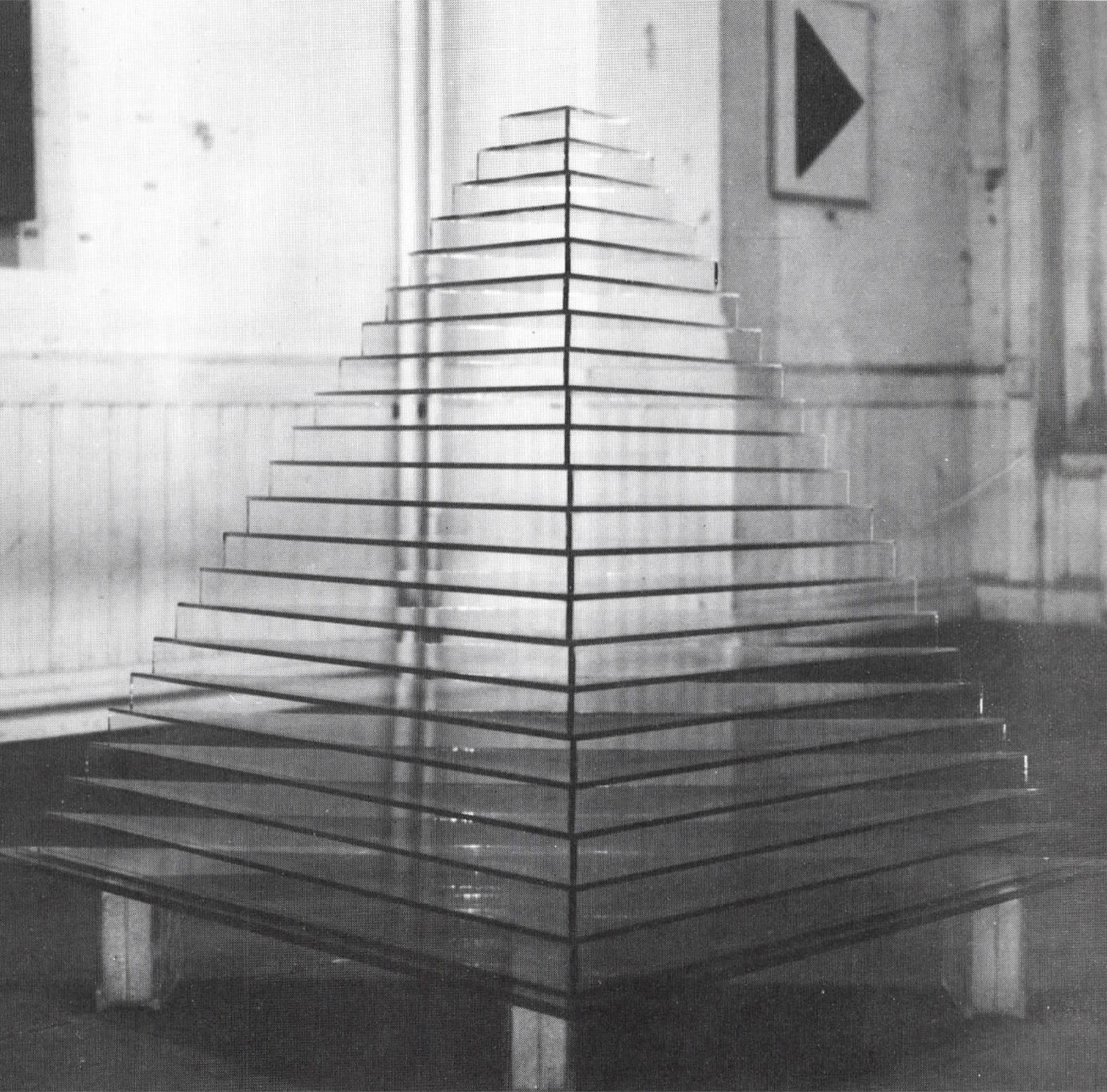

SUZANNE HARRIS

The Return of the Square, 1973

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Graffiti Van, 1973

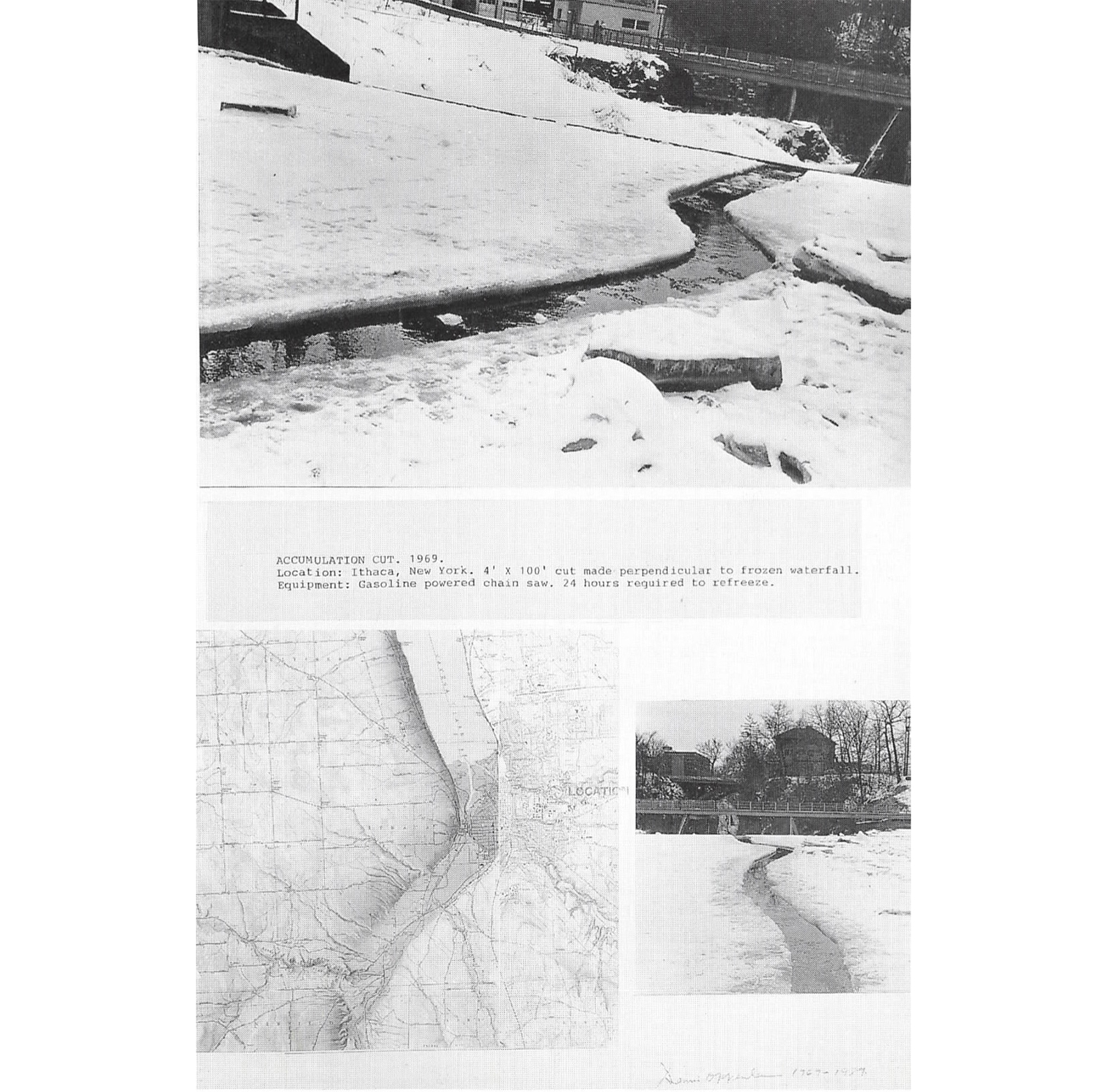

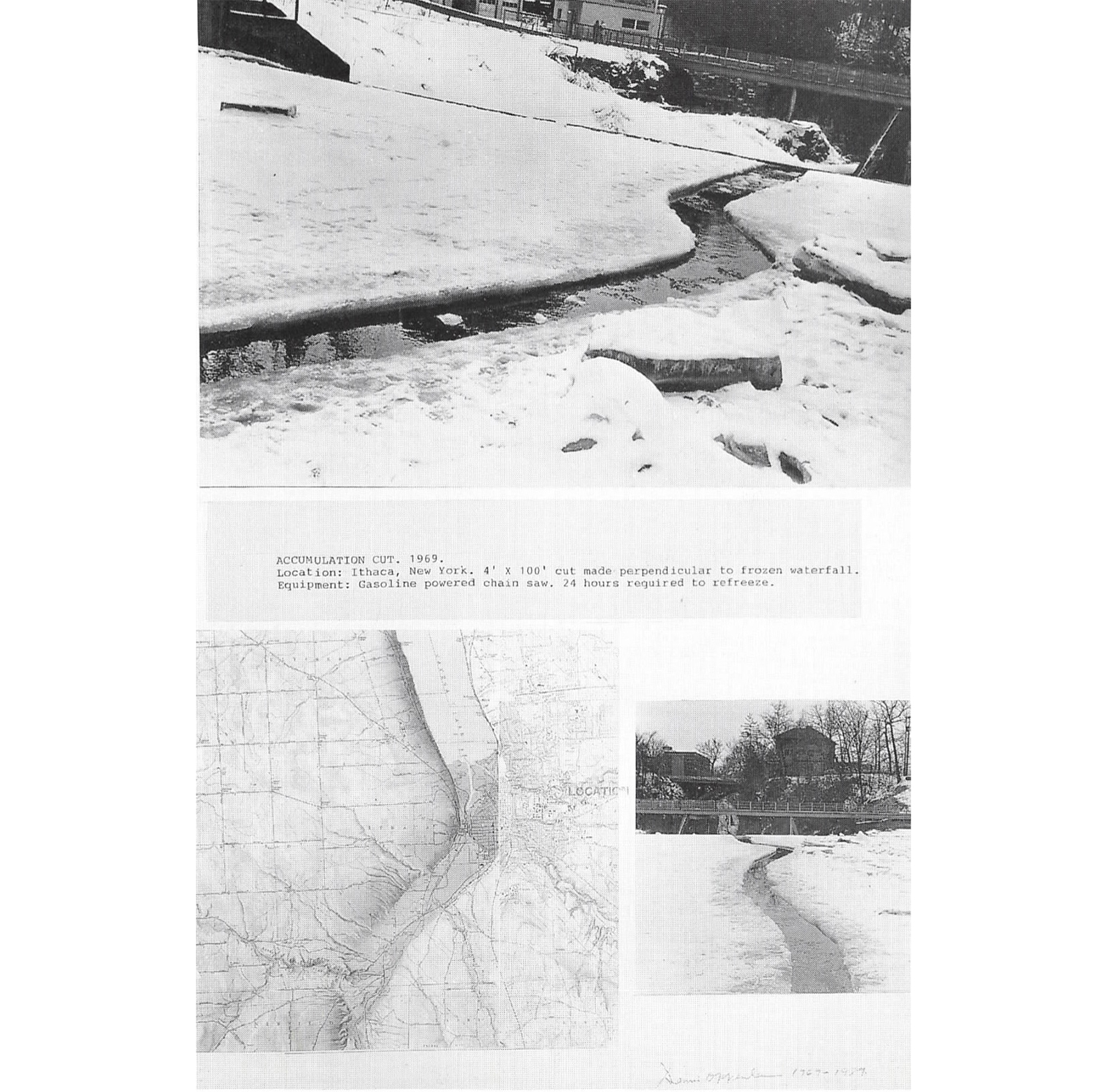

DENNIS OPPENHEIM

Accumulation Cut, 1969-89

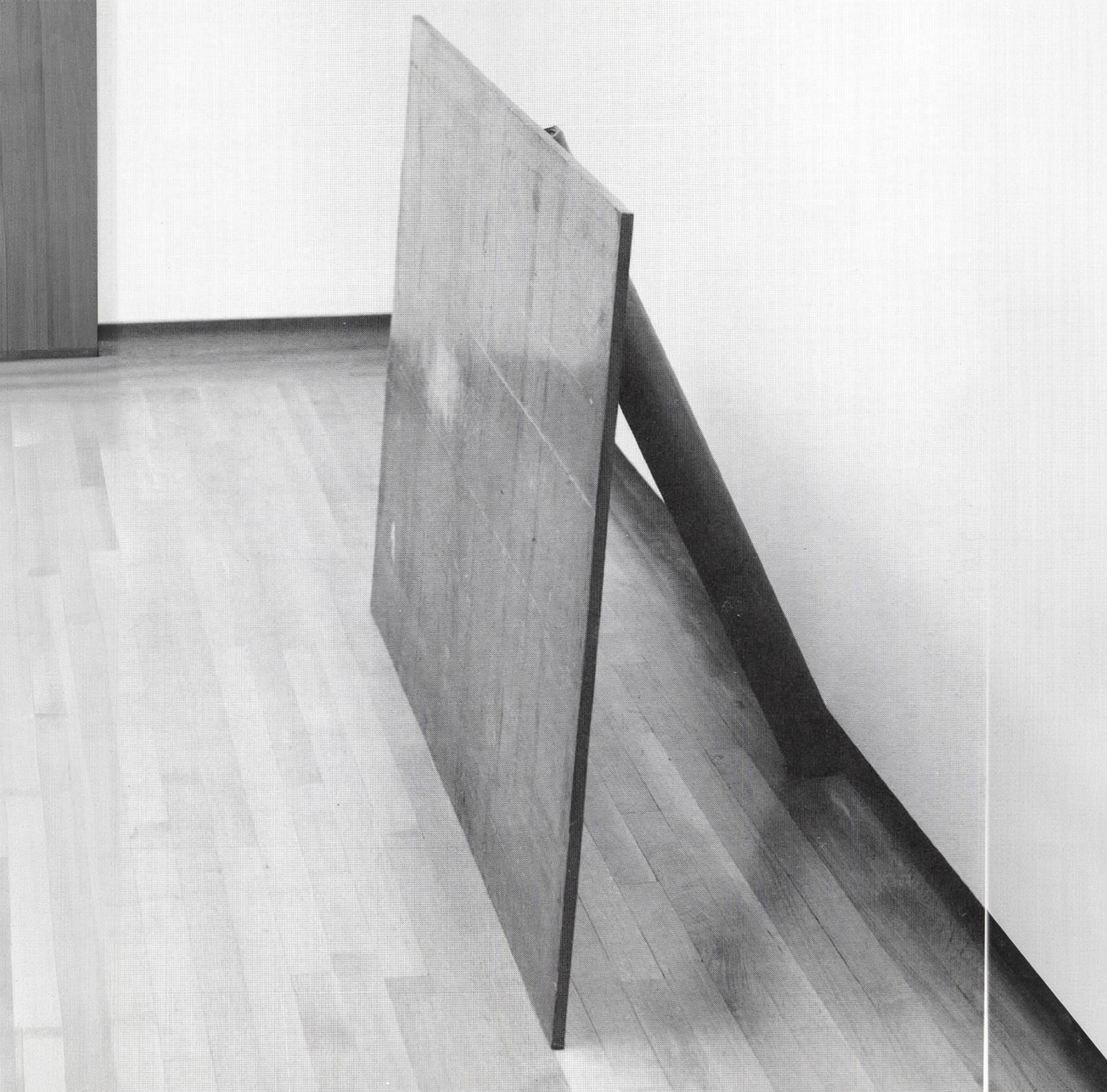

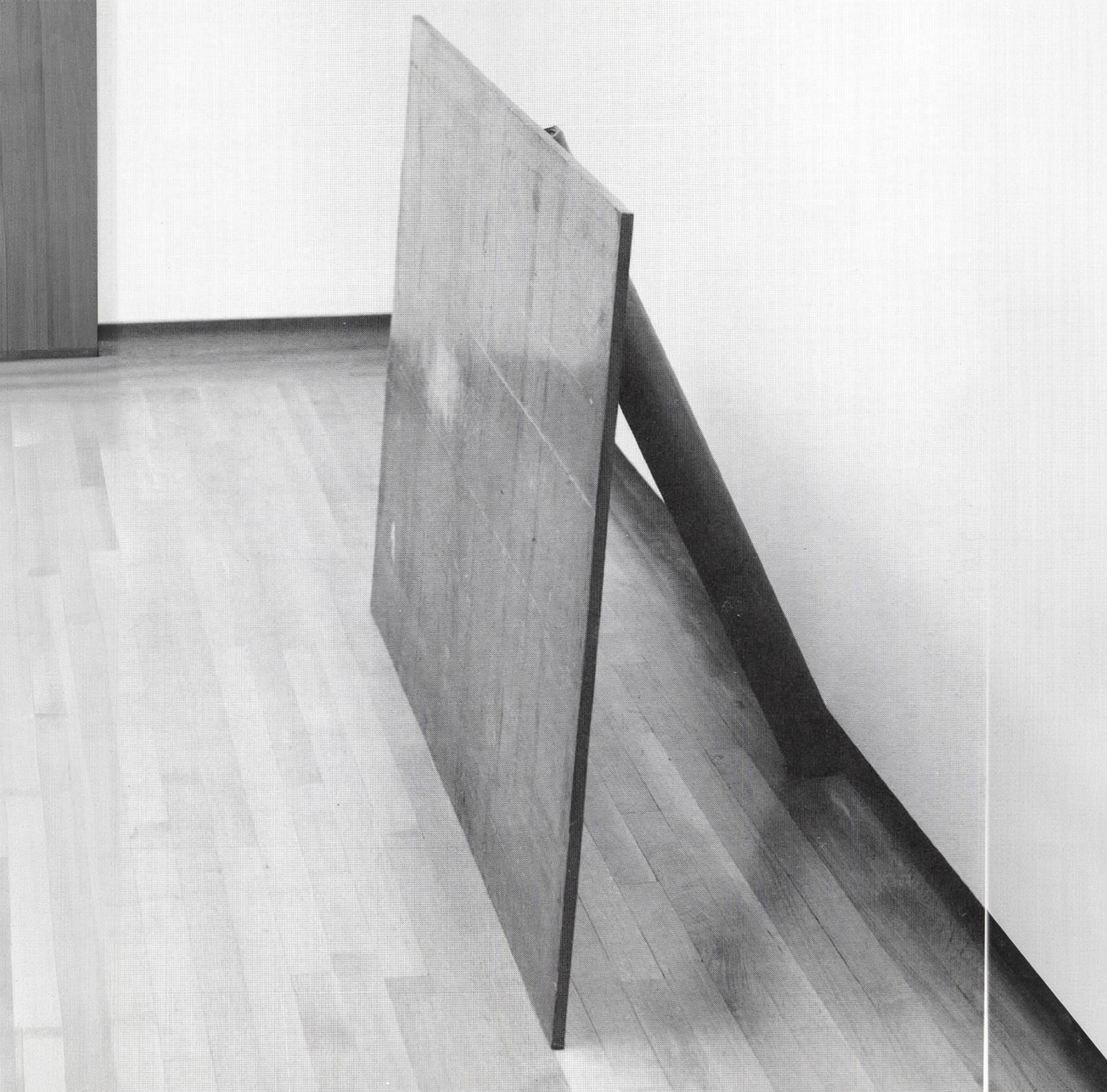

RICHARD SERRA

Lead Piece, 1969

ROBERT SMITHSON

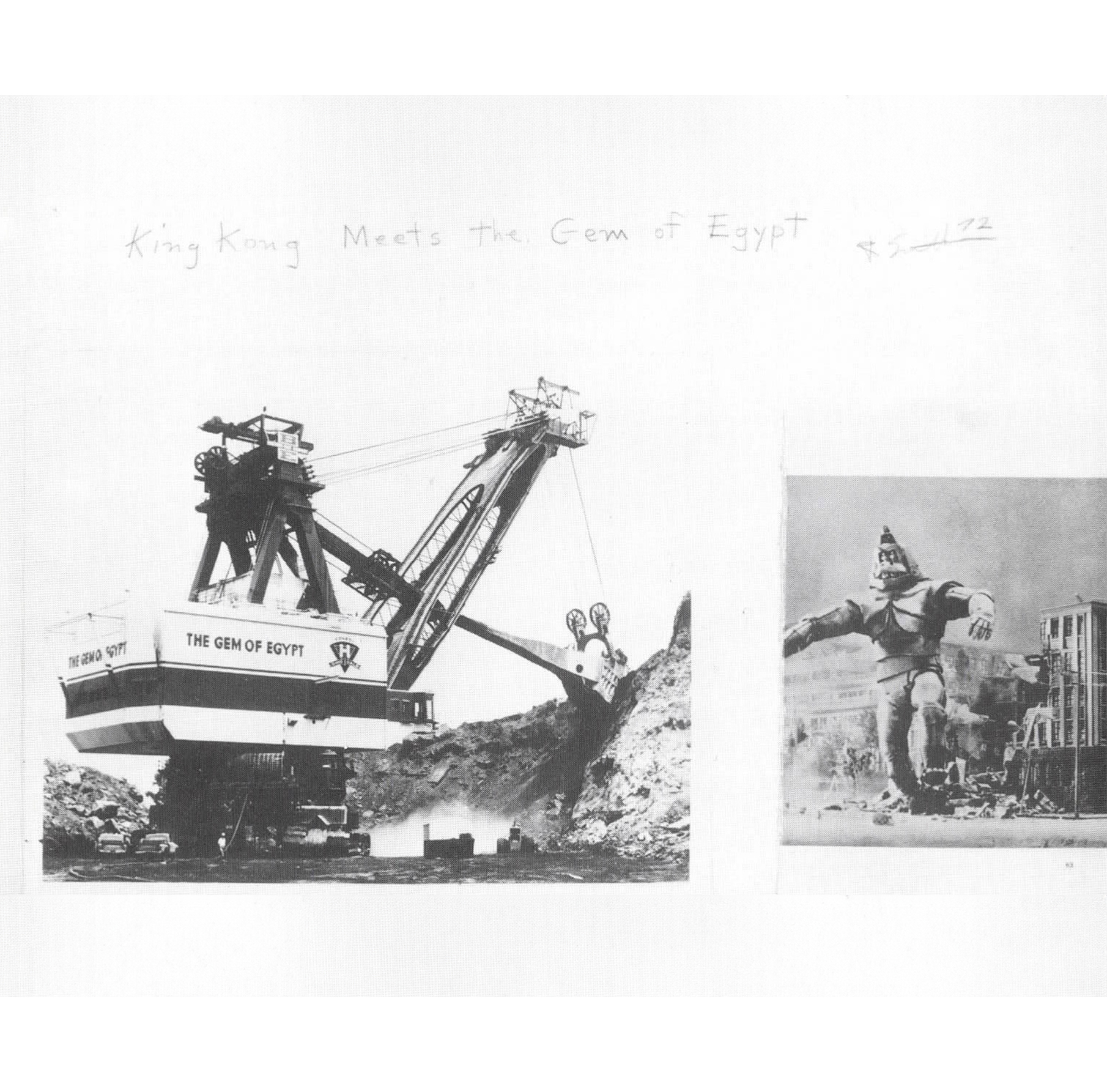

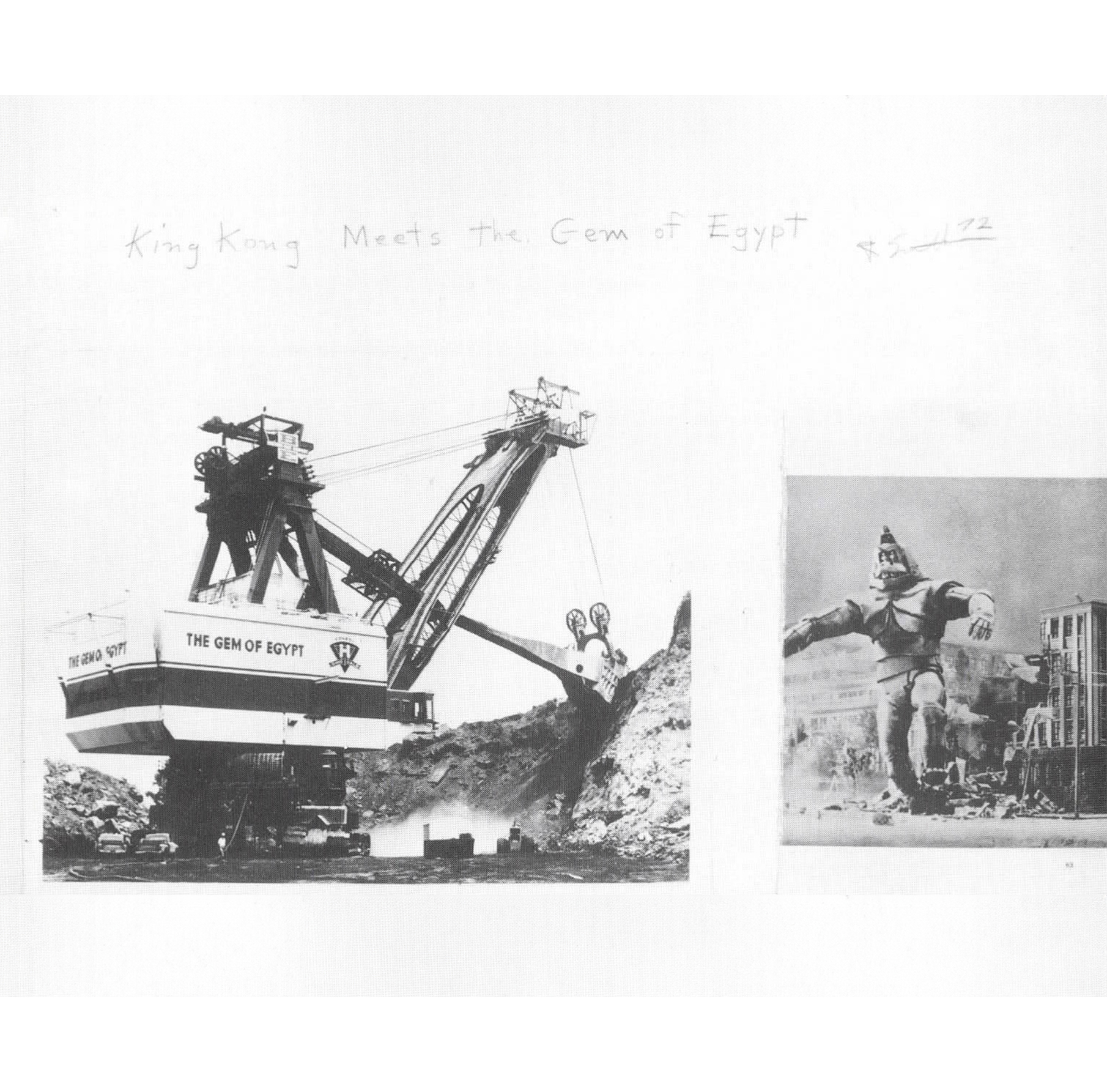

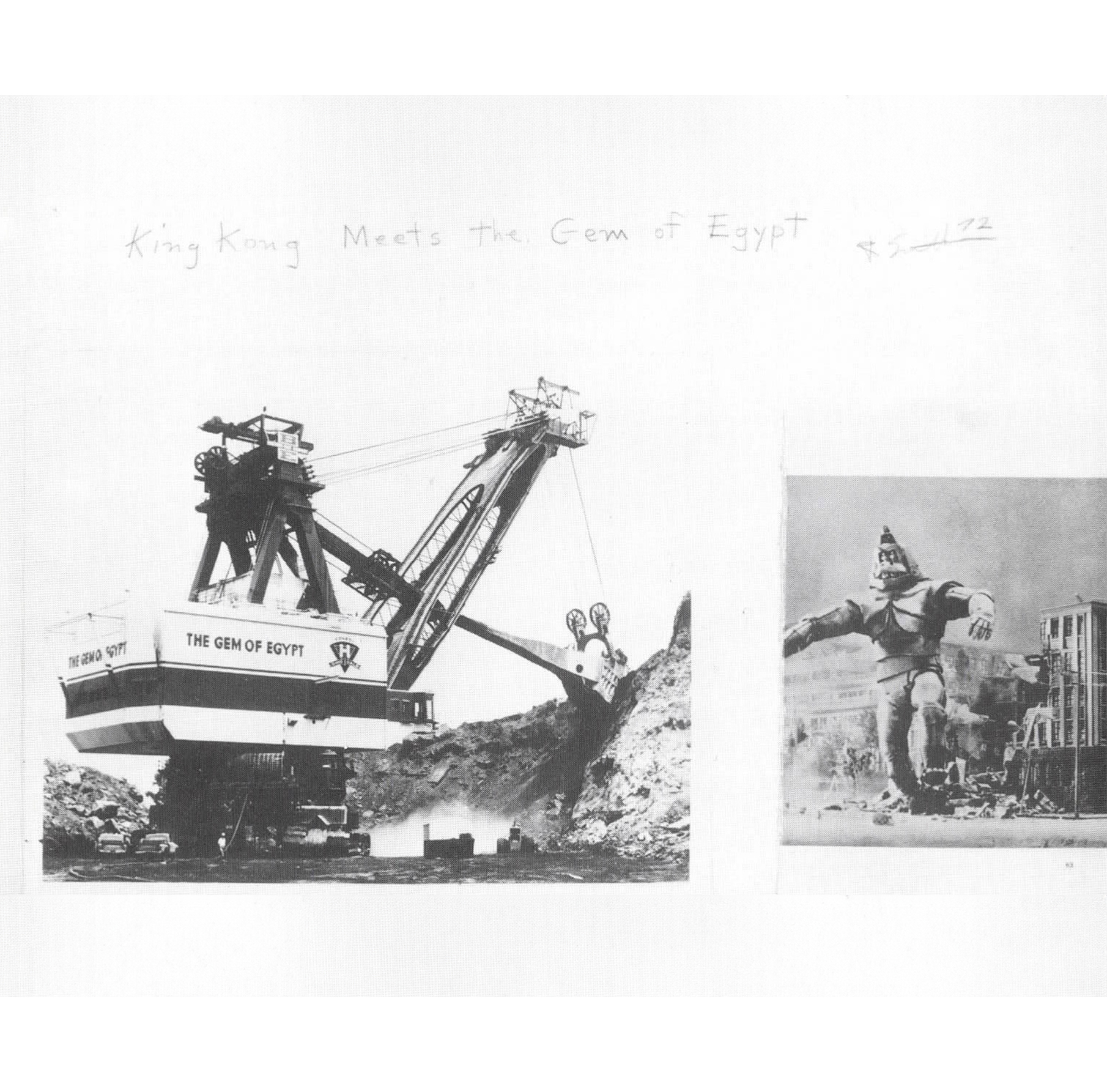

King Kong Meets the Gem of Egypt, 1972

ROBERT SMITHSON

Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors), 1969

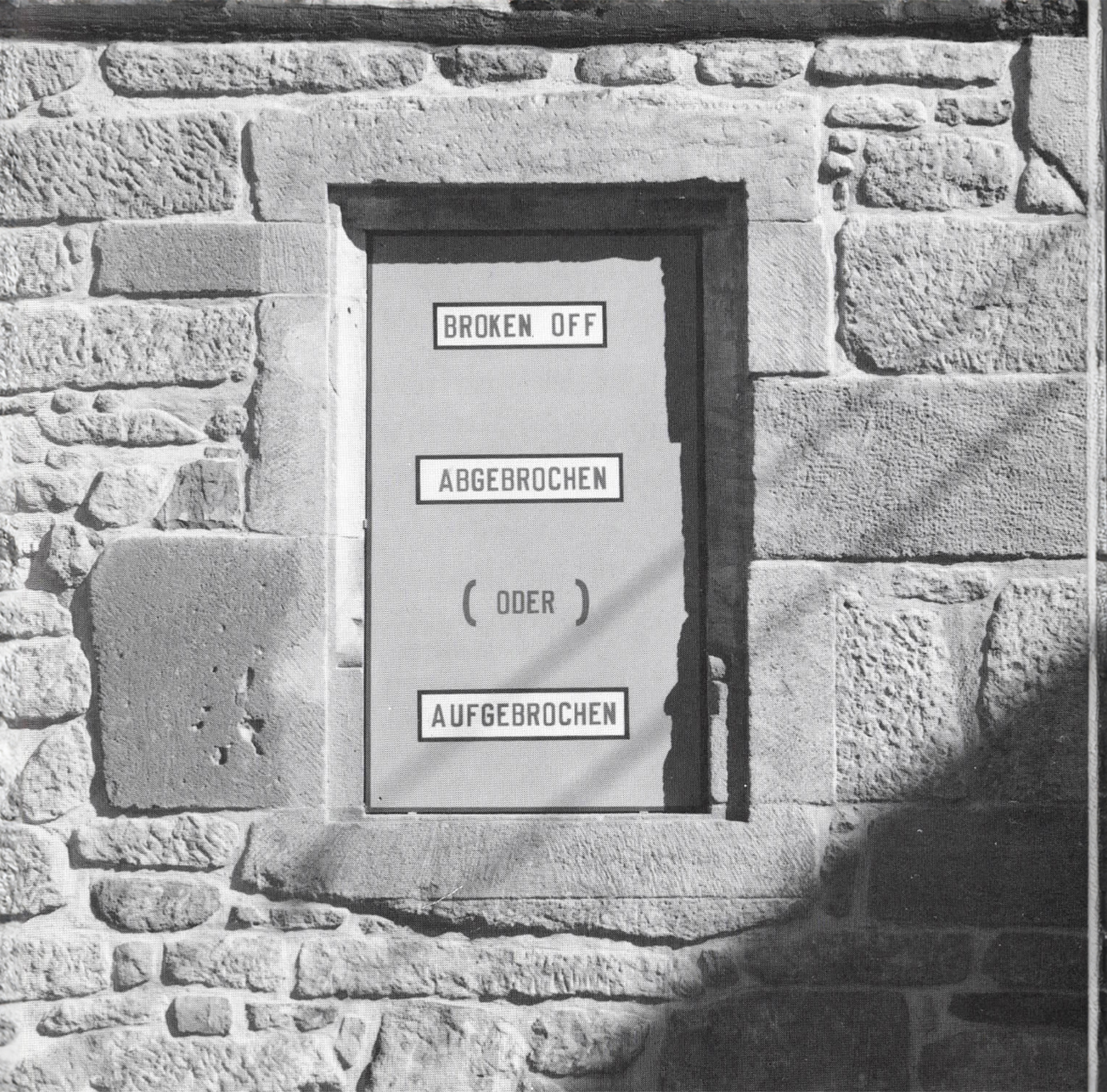

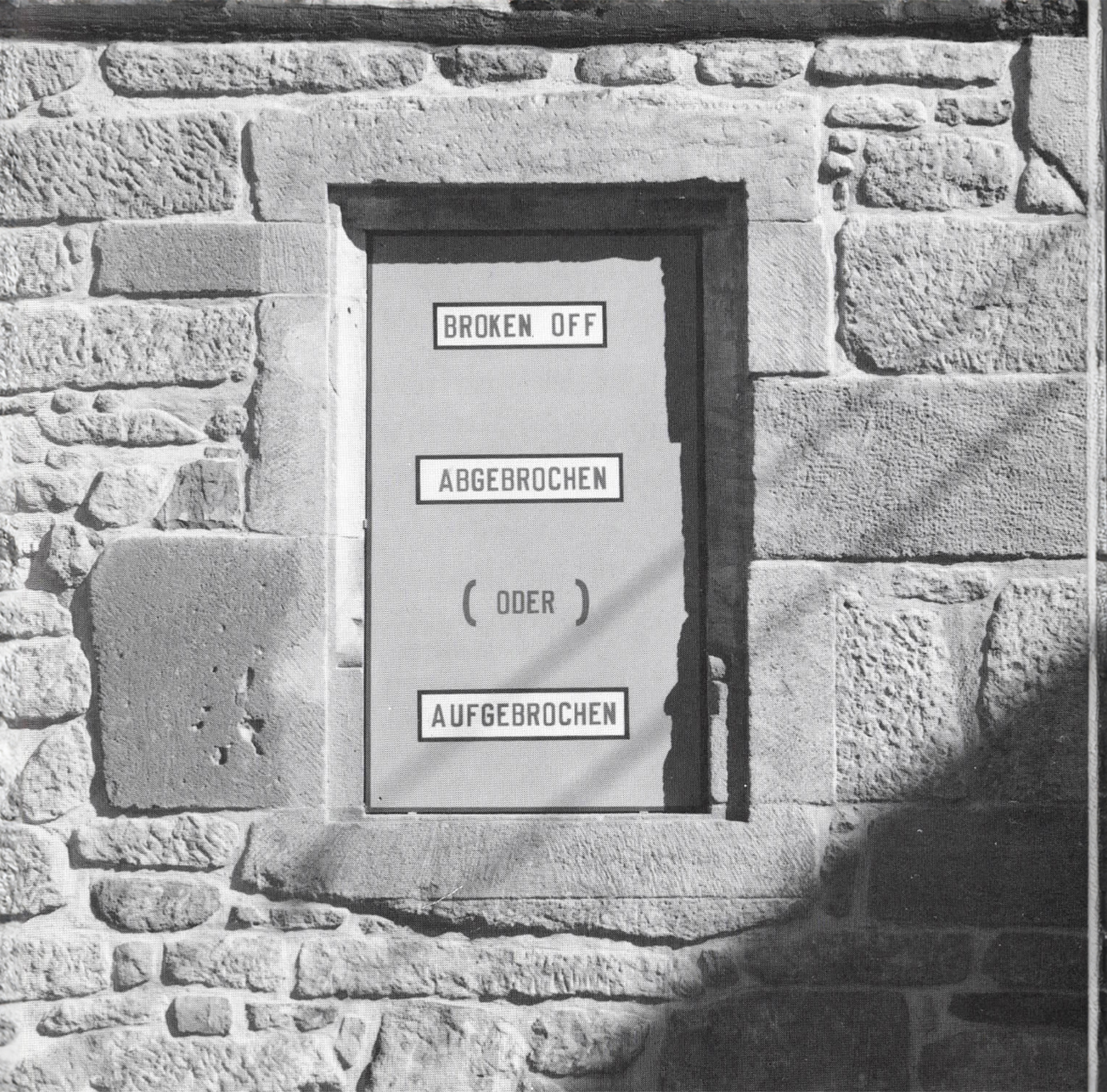

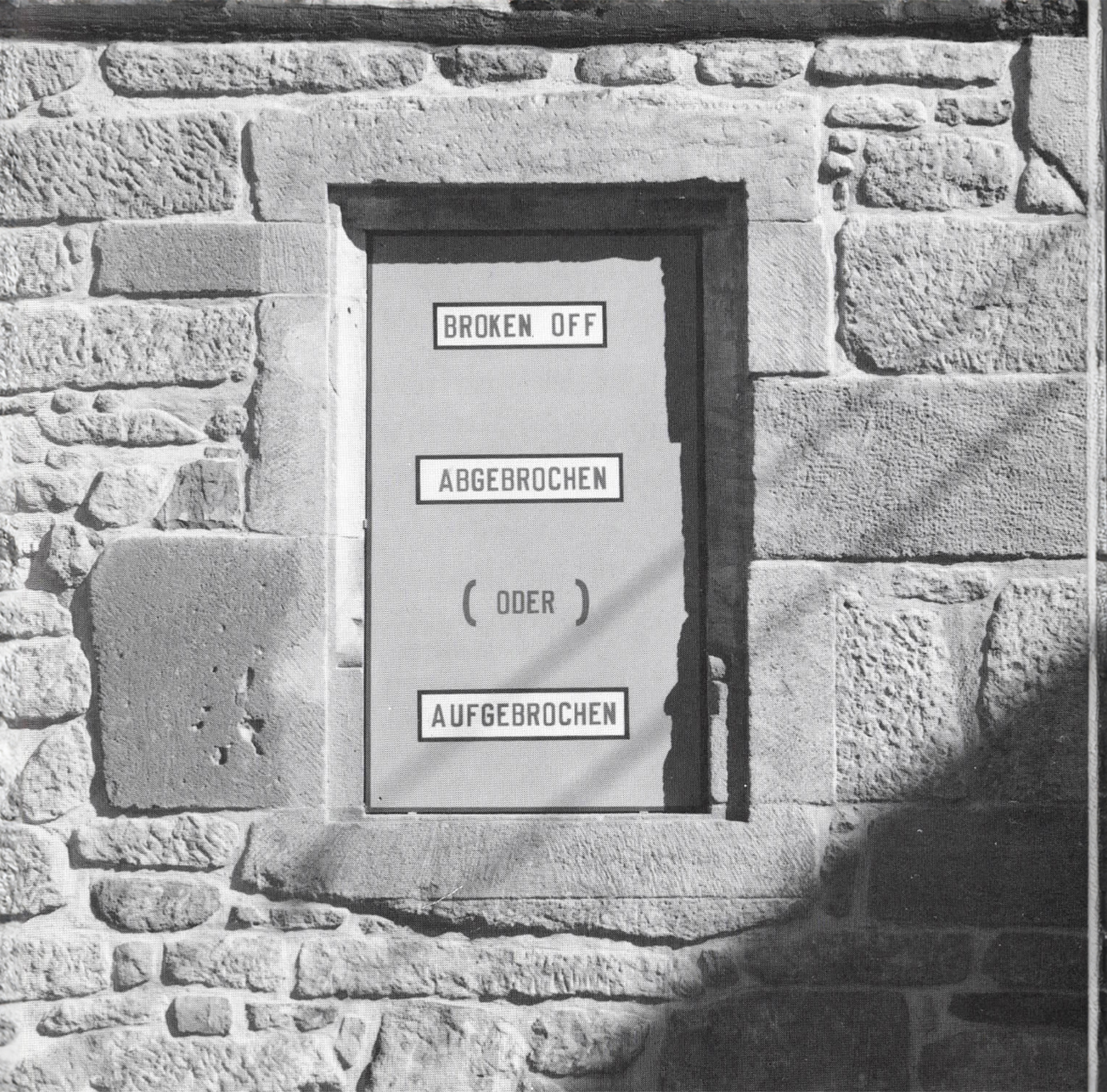

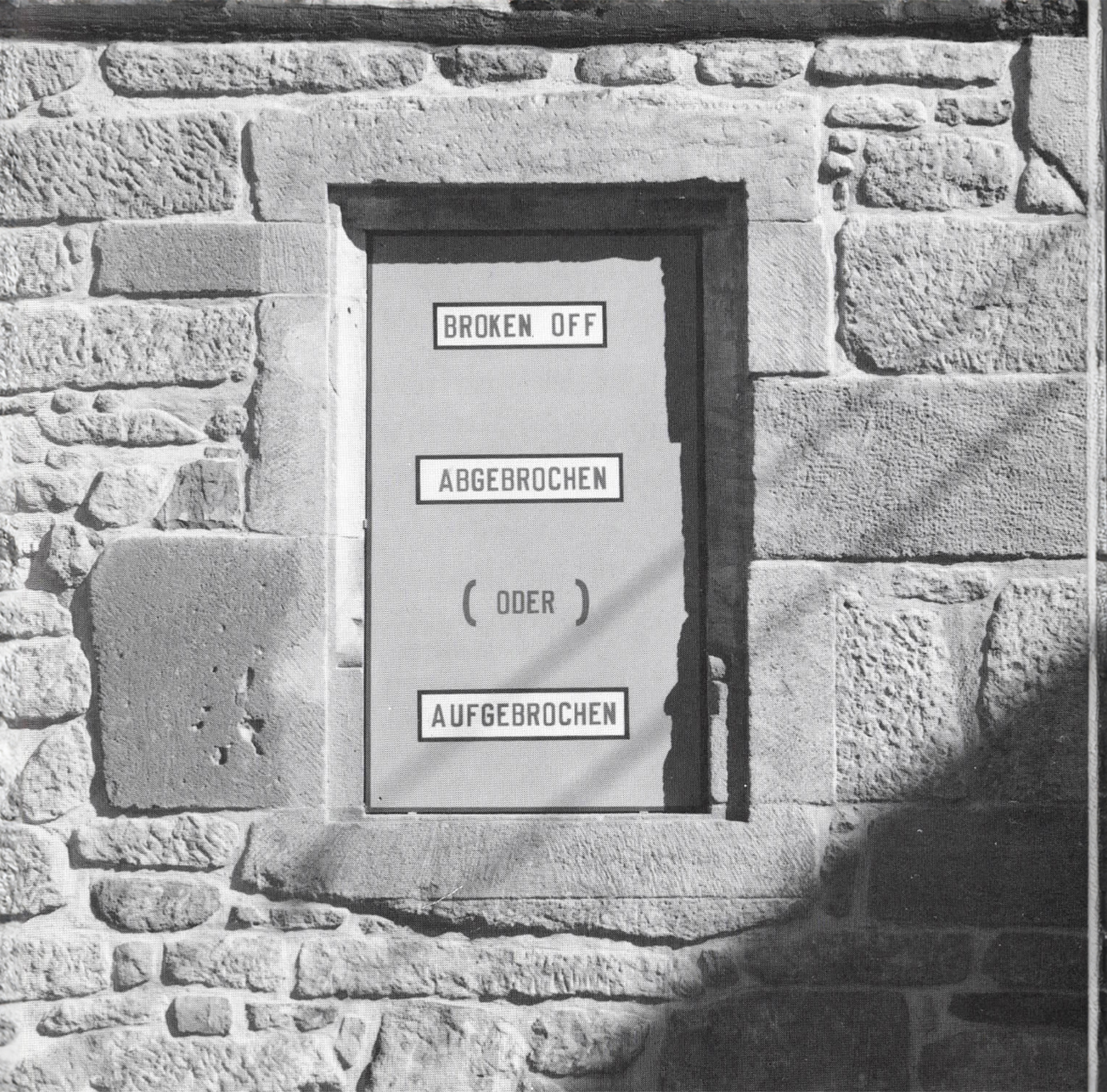

LAWRENCE WEINER

Broken Off, 1989

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Office Baroque, 1977

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

Different Henry, 1974

SUZANNE HARRIS

The Return of the Square, 1973

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Graffiti Van, 1973

DENNIS OPPENHEIM

Accumulation Cut, 1969-89

RICHARD SERRA

Lead Piece, 1969

ROBERT SMITHSON

King Kong Meets the Gem of Egypt, 1972

ROBERT SMITHSON

Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors), 1969

LAWRENCE WEINER

Broken Off, 1989

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Office Baroque, 1977

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

Different Henry, 1974

SUZANNE HARRIS

The Return of the Square, 1973

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Graffiti Van, 1973

DENNIS OPPENHEIM

Accumulation Cut, 1969-89

RICHARD SERRA

Lead Piece, 1969

ROBERT SMITHSON

King Kong Meets the Gem of Egypt, 1972

ROBERT SMITHSON

Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors), 1969

LAWRENCE WEINER

Broken Off, 1989

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Office Baroque, 1977

JOHN CHAMBERLAIN

Different Henry, 1974

SUZANNE HARRIS

The Return of the Square, 1973

GORDON MATTA-CLARK

Graffiti Van, 1973

DENNIS OPPENHEIM

Accumulation Cut, 1969-89

RICHARD SERRA

Lead Piece, 1969

ROBERT SMITHSON

King Kong Meets the Gem of Egypt, 1972

ROBERT SMITHSON

Nonsite (Essen Soil and Mirrors), 1969

LAWRENCE WEINER

Broken Off, 1989